Lifting the lockdown. Human mobility in Italy at the start of Phase 2.

Authors:

Emanuele Pepe (1), Paolo Bajardi (1), Laetitia Gauvin (1), Filippo Privitera (2), Brennan Lake (2), Ciro Cattuto (1,3), Michele Tizzoni (1)

1. ISI Foundation

2. Cuebiq Inc.

3. University of Turin

Notice: this is preliminary analysis, has not yet been peer-reviewed and is updated daily as new data becomes available. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Background

The mitigation measures enacted as part of the response to the unfolding COVID-19 pandemic are unprecedented in their breadth and societal burden. A major challenge in this situation is to quantitatively assess the impact of non-pharmaceutical interventions like mobility restrictions and social distancing, to better understand the ensuing reduction of mobility flows, individual mobility changes, and impact on contact patterns. Here, we report preliminary results on tackling the above challenges by using de-identified, large-scale data from a location intelligence company, Cuebiq, that has instrumented smartphone apps with high-accuracy location-data collection software.

Italy has been severely affected by the COVID-19 pandemic, reporting the highest death toll in Europe as of April 2020. Following the identification of the first infections, on February 21, 2020, national authorities have put in place an increasing number of restrictions aimed at containing the outbreak and delaying the epidemic peak. On March 12, the government imposed a national lockdown. On May 4, the lockdown has been lifted - although mobility restrictions are still in force - and many business acitivities have restarted.

Here, we present the first assessment of mobility patterns in Italy after the easing of the lockdown, at the sub-national scale.

Data

Mobility data is provided by Cuebiq, a location intelligence, and measurement platform. Through its Data for Good program, Cuebiq provides access to aggregated and privacy-safe mobility data for academic research and humanitarian initiatives. This first-party data is collected from anonymized users who have opted-in to provide access to their location data anonymously, through a GDPR-compliant framework.

Location is collected anonymously from opted in users through smartphone applications. At the device level, iOS and Android operating systems combine various location data sources (e.g. GPS, wifi, beacons, network) and provide geographical coordinates with a given level of accuracy. Location accuracy is determined by the device and is variable, but can be as accurate as 10 meters.

Temporal sampling of anonymized users’ location is also variable and dependent on app/OS characteristics and on user behavioral patterns, but it has a high-frequency overall. We remove short-time dynamics by aggregating the data over 5-minute windows. The basic unit of information we process is an event of the form (anonymous hashed user id, time, latitude, longitude), plus additional non-personal metadata and location accuracy.

For a more detailed description of the underlying data, please see the page Data.

Methods

From the original location data, we derive three epidemiologically relevant metrics of mobility and proximity that capture both long-range and short-range mobility patterns:

- the weekly origin-destination matrices measuring users’ movements between Italian provinces;

- the weekly users’ average radius of gyration by province, capturing the extent of individual movements;

- the daily average degree of users’ proximity network, capturing the level of social distancing by province.

All these metrics are computed by aggregating the original data sources in space and time in order to comply with privacy principles that ensure users cannot be re-identified, even indirectly, from the data.

A more detailed description of how these metrics have been generated can be found in the preprint:

Pepe, E., Bajardi, P., Gauvin, L., Privitera, F., Lake, B., Cattuto, C., & Tizzoni, M. (2020).

COVID-19 outbreak response: a first assessment of mobility changes in Italy following national lockdown.

medRxiv: https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.03.22.20039933v1

Summary of results

At the national level, mobility patterns have increased across the whole country, but have remained below the baseline levels (we consider the period from January 18 to February 21 as our baseline). Average mobility and proximity metrics have reached levels similar to those that were observed at the beginning of the week of March 9-15, that is immediately after the first nationwide stay-at-home order was issued (March 8).

Users’ movements between different provinces are now at -48%, on average, with respect to the baseline. The increase in mobility has mainly occurred between provinces within the same regions. During the lockdown, the largest average reduction observed was -71% at the national level. In the following, we consider the week of March 23-29, as the most representative of the lockdown, when the most restrictive policies were enforced in full (closure of several industries).

The median radius of gyration has increased in all provinces. On average, the radius of gyration has reached levels that are -73% below baseline. During the lockdown, the largest average reduction observed was -91%.

The average degree of the proximity network, at the national level, has reached levels equal to -40% with respect to the baseline.

While the radius of gyration has remained at very low levels, the degree of the proximity network has increased more quickly, suggesting that lifting the lockdown has led to an increase in short-range mobility rather than in long-range mobility.

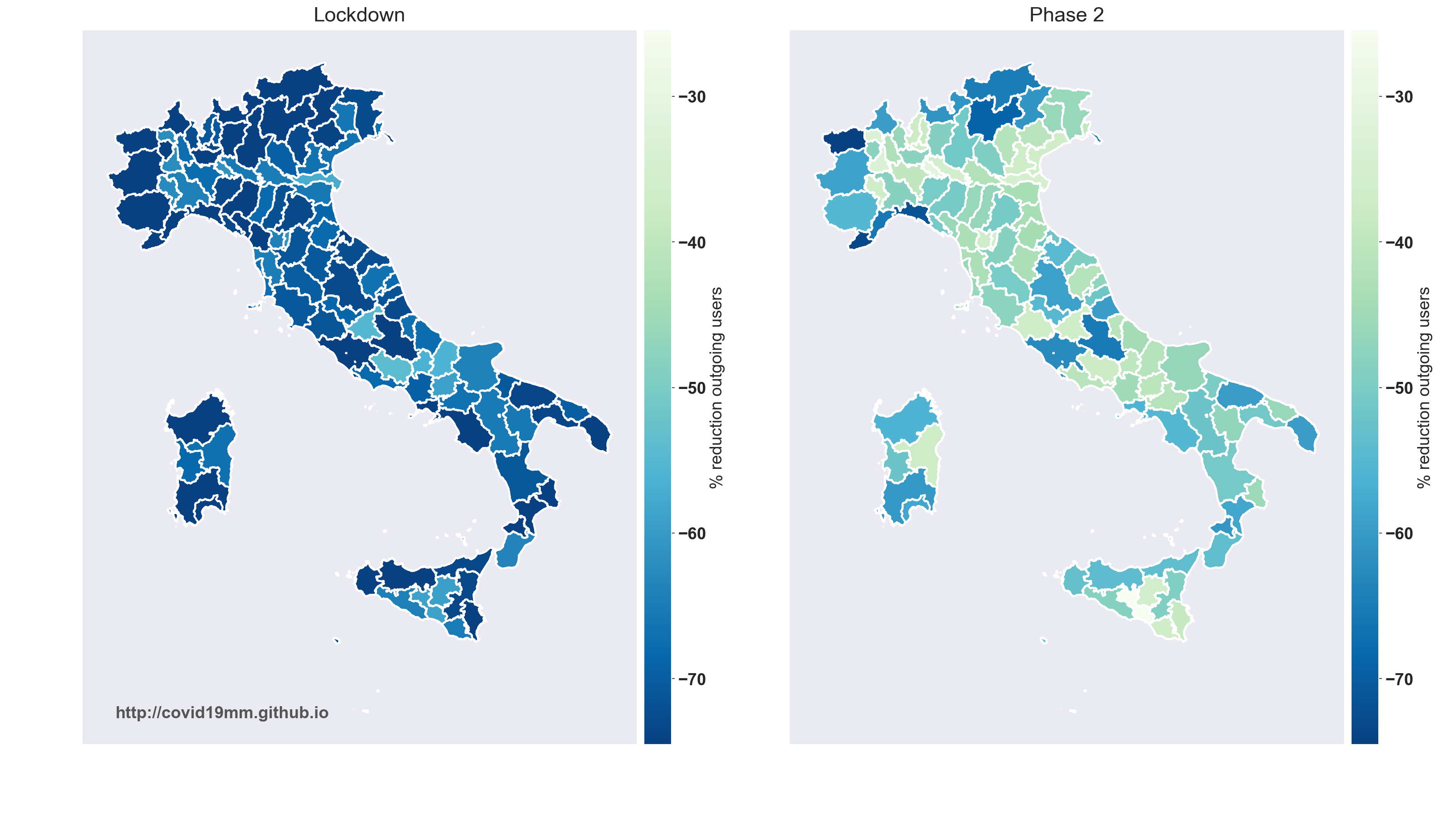

Movements between provinces

The figure below compares the weekly fraction of users traveling out of the Italian provinces during the lockdown (left) and in the first week of Phase 2 (right).

Movements between provinces have not increased uniformly across the country. In some provinces, like Aosta, Genova, and Rome, outgoing movements have remained below -60% with respect to baseline. In some other provinces, outgoing movements have reached -35% or more with respect to baseline levels: Caltanissetta, Lodi, Vercelli, Rovigo. Notably, some provinces have seen a rebound of more than 30 percentage points in traffic. For instance, movements out of the province of Monza have risen from -73% to -37%, with a net increase of 36 percent points. Other provinces of Lombardy - Lecco and Como - have seen similar strong increases of 30 percent points or more.

We also observe significant heterogeneities by looking at specific mobility connections between provinces. Movements have increased significantly between neighboring provinces in the Veneto, Piedmont and Friuli regions, as shown in the table below. The table displays the 10 connections with the largest relative increase in mobility during the first week of Phase 2. Reductions are computed with respect to the baseline levels of January-February 2020.

| Province of Origin | Province of Destination | Lockdown reduction | Phase 2 reduction |

|---|---|---|---|

| Padova | Rovigo | -69% | -27% |

| Rovigo | Padova | -68% | -35% |

| Alessandria | Asti | -52% | -29% |

| Asti | Alessandria | -55% | -33% |

| Vicenza | Verona | -75% | -37% |

| Verona | Vicenza | -73% | -41% |

| Biella | Vercelli | -68% | -37% |

| Vercelli | Biella | -67% | -38% |

| Pordenone | Udine | -72% | -40% |

| Udine | Pordenone | -72% | -41% |

On the contrary, mobility between provinces in different regions remained very low with respect to baseline levels, as expected since inter-regional mobility is still restricted by law. The only exception is the mobility between Savona and Genova which has increased slightly altough the two provinces belong to the same region. The table below shows the 10 connections with the smallest increase in mobility during the first week of Phase 2.

| Province of Origin | Province of Destination | Lockdown reduction | Phase 2 reduction |

|---|---|---|---|

| Milano | Torino | -94% | -82% |

| Torino | Milano | -94% | -80% |

| Brescia | Trento | -91% | -80% |

| Trento | Brescia | -89% | -79% |

| Trento | Verona | -85% | -75% |

| Verona | Trento | -88% | -75% |

| Savona | Genova | -86% | -74% |

| Genova | Savona | -88% | -72% |

| Alessandria | Genova | -82% | -73% |

| Genova | Alessandria | -81% | -72% |

Overall, the median of users’ movements on connections within the same region has increased from -77% to -53%. The median of users’ movements on connections between provinces of different regions has increased from -85% to -71% only.

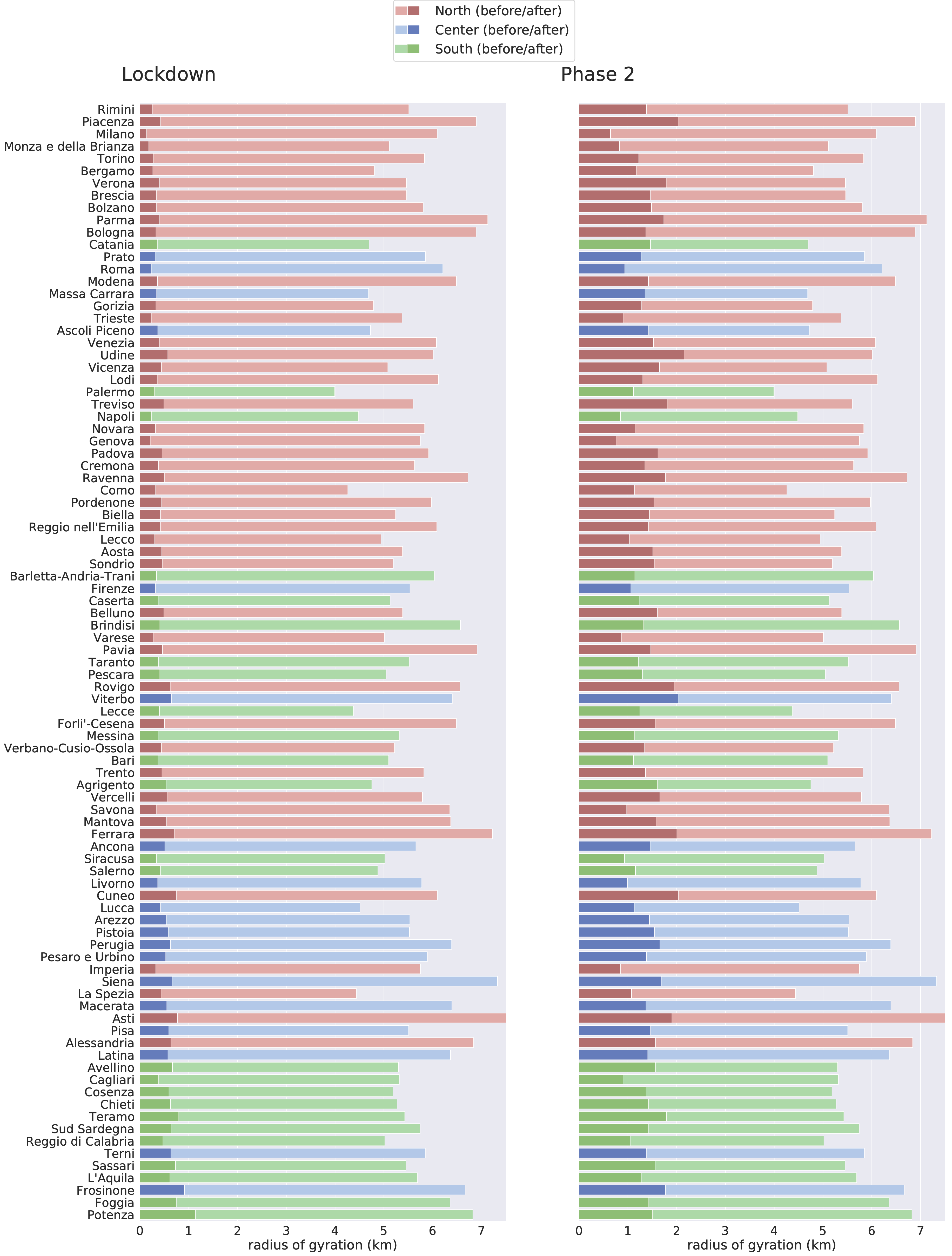

Radius of gyration

The figure below compares the median weekly radius of gyration of our users by province, during the lockdown (left) and in the first week of Phase 2 (right). The shaded bar indicates the baseline median values. Provinces are ranked by the relative increase of the radius of gyration during the Phase 2, with respect to the lockdown, from the largest (top) to the smallest (bottom).

Although, absolute values of the radius remained small, the largest relative increase in the radius of gyration was generally observed in the provinces of Northern Italy: Rimini, Piacenza, Milano, Monza, Torino among the top ones. In those provinces, the radius of gyration has increased more than 3-fold.

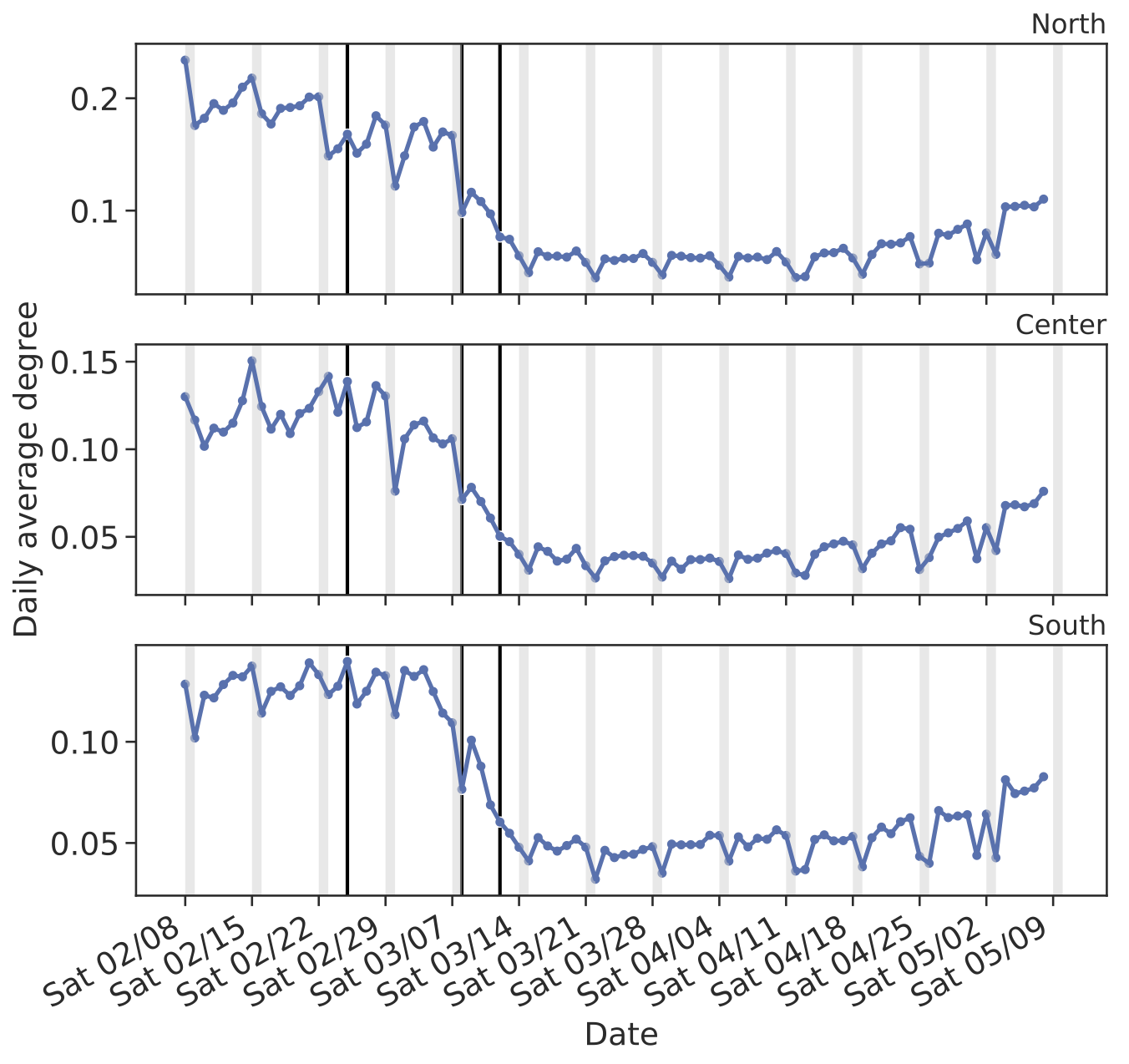

Proximity network

The average degree of the proximity network, <k>, shows an increasing trend in all regions since the second half of April.

Overall, the values of <k> remained below the baseline levels.

After the lift of the lockdown, the average degree has increased to -44% below baseline in the North, -36% in the Center and -34% in the South.

As reported in our latest update, on April 12, Easter Day, the average degree of all users was 86% lower than the pre-outbreak averages in the North, 83% in the Center and 82% in the South and the Islands.

Thus, the density of the proximity network has increased relatively more in the South and in the Center than in the North.

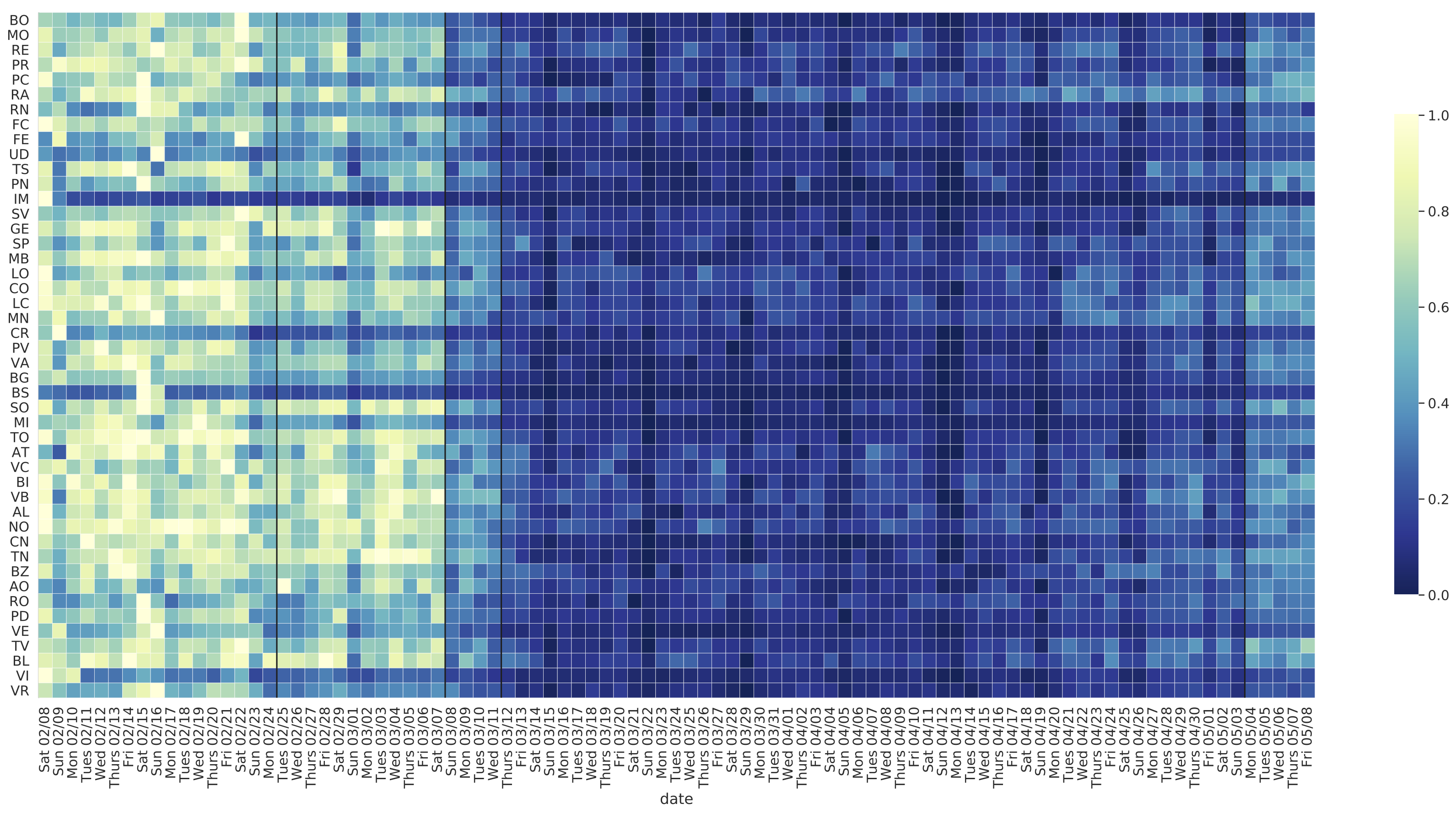

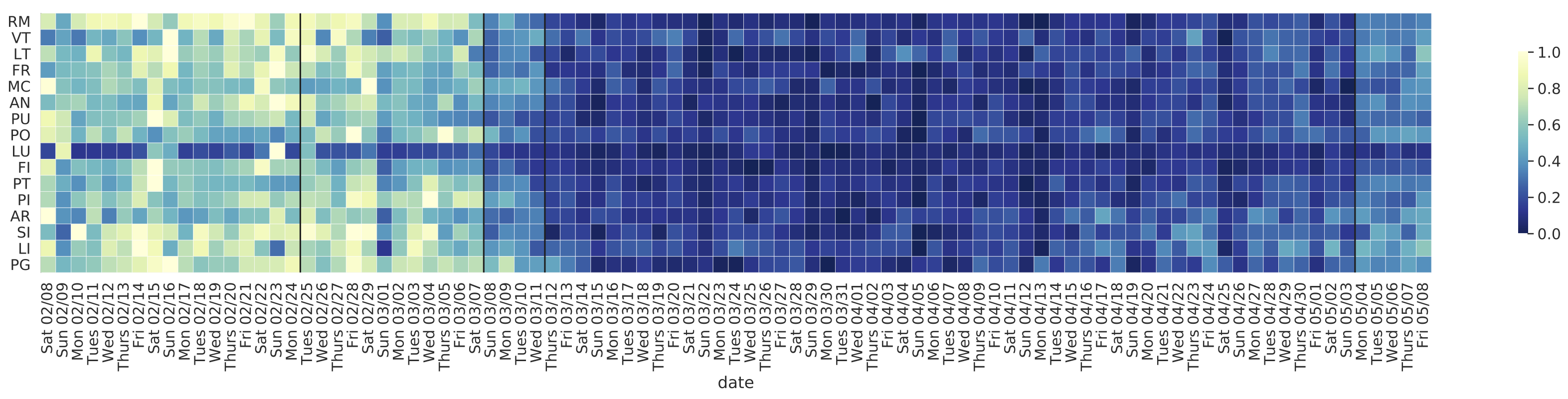

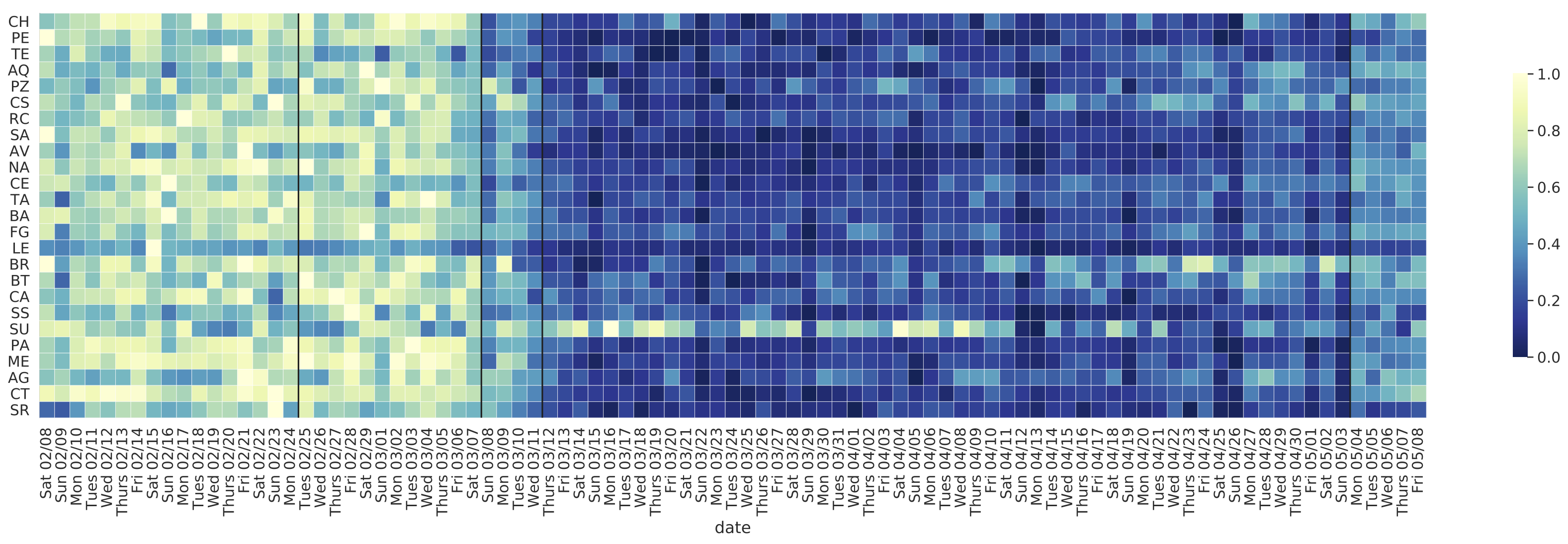

The heatmaps below show the time evolution of the average degree of the proximity network by province.

Northern Italy

Central Italy

Southern Italy

Data Protection

This research was solely based on data from anonymized users who have opted-in to provide access to their location data anonymously, through a GDPR-compliant framework. The analysis never singled out identifiable individuals and no attempts were made to link these data to third party data about an individual. In order to preserve privacy, residential areas are inferred at an aggregated geohash level, thereby allowing for demographic analysis while obfuscating the true home location of anonymous users and prohibiting misuse of data.

Acknowledgments and Partnerships

This preliminary analysis is a collaboration between the ISI Foundation and Cuebiq Inc. Authors at ISI Foundation acknowledge support from the Lagrange Project funded by CRT Foundation and thank Cuebiq for access to a de-identified sample of its mobility data. In response to the COVID-19 crisis, Cuebiq is providing insights to academic and humanitarian groups through a multi-stakeholder data collaborative for timely and ethical analysis of aggregate human mobility patterns.